Regular readers of Pulp Curry may be familiar with the name Iain McIntyre, my co-editor on Girl Gangs, Biker Boys and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950-1980, and its follow up, Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950-1980, out sometime in 2019. Iain is also the editor of a number of his own books, the most recent of which, On the Fly! Hobo Literature & Songs, 1879-1941, has just come out through PM Press. On the Fly! is an anthology which brings together dozens of stories, poems, songs, stories, and articles produced by hoboes to create an insider history of the subculture’s rise and fall. Iain was good enough to answer a few questions about his latest book, researching hobohemia, and the links between hobo culture and crime writing.

Regular readers of Pulp Curry may be familiar with the name Iain McIntyre, my co-editor on Girl Gangs, Biker Boys and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950-1980, and its follow up, Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950-1980, out sometime in 2019. Iain is also the editor of a number of his own books, the most recent of which, On the Fly! Hobo Literature & Songs, 1879-1941, has just come out through PM Press. On the Fly! is an anthology which brings together dozens of stories, poems, songs, stories, and articles produced by hoboes to create an insider history of the subculture’s rise and fall. Iain was good enough to answer a few questions about his latest book, researching hobohemia, and the links between hobo culture and crime writing.

One of the points you make in the introduction to On the Fly! is that while there have been a lot of historical and academic studies about American hobo culture, there is very little currently available in the words of the members of the culture themselves. Where did you get the inspiration for this book?

I’d long been aware of hobohemia’s influence on American popular culture via country and folk music songs, Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character, etc but it wasn’t until I met some modern train hoppers in the 1990s that my interest was really piqued. After reading Kenneth Alsop’s classic study Hard Travelling and Todd De Pastono’s Citizen Hobo I came to understand just how huge the subculture had been, with literally millions of people riding the rails from the 1870s to 1940s, and what a key role migratory workers had played in American industry and agriculture as well as radical politics.

In reading these I also learnt about the many memoirs, novels, short stories, academic studies, etc that had been published during the period and the impact these had on sociology, hard boiled fiction, etc. Works such as The Road, by socialist and adventure writer Jack London and You Can’t Win, by burglar and stick-up man Jack Black, had been reprinted but little else. Although Jim Tully, Josiah Flynt and Leon Livingston had sold a ton of work in their day most, if not all, of their work was out of print. As I dug deeper I found that many of these first-hand views of hobo life were fascinating, thrilling and hilarious. As a result I figured a comprehensive anthology focused on works created during the subculture’s peak years by hoboes and others who had rode the rails was in order.

The culture you are chronicling stretches from around the 1870s to the outset of World War II. Can you tell me about the origins of this culture and what killed it?

A number of factors gave rise to the hobo, key amongst them the economic and social realities of the time for working Americans. There was a need for large amounts of highly mobile labour to pick crops, cut trees, build infrastructure, etc but no desire to properly pay those involved or to allow them to stick around once the job was done. Urban and rural working life was generally a drudge and there were intermittent periods of mass employment. With the construction of hundreds of thousands of miles of railway people who previously didn’t have the means of travel gained a simple, albeit risky, way to travel in search of work and adventure.

Once they started congregating in ‘jungle’ camps by the side of water tanks and other train hopping spots and in ‘skid rows’ and ‘main stems’ in the cities a lifestyle with its own argot, mores, haunts, politics and music bubbled up. All of which garnered extra interest from a society which was already either vilifying hoboes for their poverty and footloose ways, or celebrating them as an embodiment of American mobility. Whilst journalists, pulp hacks, filmmakers and cartoonists tended to wildly distort, pity and degrade the subculture, this hunger for information provided some of those within it with an opportunity to get published and recorded, to have their voices and music heard. Because the lifestyle left a lot of time to kill, hobo writers and musicians already came armed with songs and stories that had been long honed around the campfire and proven their worth.

By the 1920s some declared that the age of the hobo was over. Agricultural work was diminishing as farmers responded to the increasing wages through mechanisation and the economy was doing its best for a long time. Cars were becoming cheap enough for migratory workers to buy so there was a process of individualisation as people weren’t congregating together as much in boxcars, jungles, etc. The Depression brought hundreds of thousands, if not millions back to the boxcars, including an enormous number of unaccompanied or abandoned teenagers. With the advent of World War Two and the long boom that followed it the lifestyle withered for all but die hard enthusiasts.

Where did you find the material in this book?

Where did you find the material in this book?

Quite a few academic studies had been already been written when I first got interested in the topic and new ones came out fairly regularly over the twenty odd years I was compiling material, so I was able to put together an extensive list of material based on their bibliographies. A good chunk of the things included in the book I found in the British Library, which has full collections of things like American Mercury, a magazine which in its early years cast a critical eye on American society, and which gave early breaks to hobo writers who became established like Jim Tully and George Milburn, as well as others who remained unknown. Between there, Amsterdam’s International Institute of Social History and other libraries I was able to source a number of memoirs, novels and periodicals. The motherlode was discovering that the St Louis Public Library had a near complete run of the Hobo News, a magazine that was bankrolled by a millionaire who spent his fortune on the newspaper as well as setting up Hobo Colleges which were part library, part debating societies, part accommodation and part drop-in centres. The library was happy to send me a microfilm for the cost of reproduction. Over time some stuff started turning up on the internet and I also bought a number of books from second-hand stores and online sellers.

What criteria did you apply for selecting material?

I wanted to include works that addressed all the key parts of the lifestyle- hopping trains, avoiding or confronting railway and town cops, hustling, going to jail, engaging in strikes and sabotage, begging, going hungry, going on sprees, sleeping in flophouses, barns and the outdoors, enduring religious services to get a feed, working all kinds of jobs from mining to repairing umbrellas and washing dishes, etc. The goal was also to be representative in terms of covering these subjects from a number of different perspectives and styles of writing. Thankfully I had such an abundance of material that I was able to find engaging literature, songs and poems that covered all of this as well as relevant photos, cartoons and illustrations.

I am sure readers of Pulp Curry would be particularly interested to know, did any of the authors included in this book produce crime writing?

Following the nineteenth century’s ‘Tramp Scare’, during which mainstream newspapers and commentators fulminated to the point of advocating that weary traveler’s be sterilised and eradicated, most aspects of hobo life were criminalised. As a result many songs and stories deal with petty crime, mainly in the form of minor theft, vagrancy and so on, as well as avoiding, escaping and battling town and rail police.

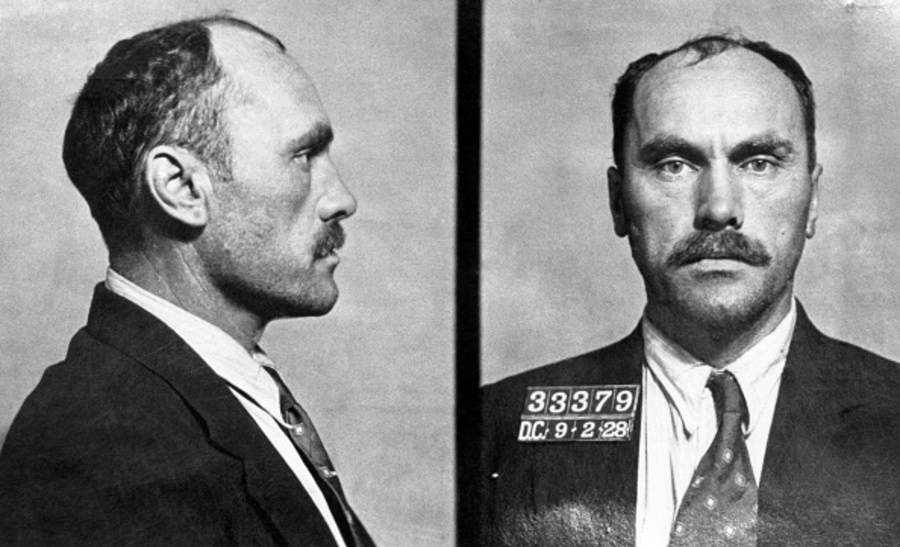

Within hobohemia there were also career criminals known as ‘Yeggs.’ In the days before cars became available, safe crackers, professional burglars and armed robbers would often travel from place to place as well as skip town via boxcars. Others, known as ‘hijacks’ operated by “harvesting the harvesters”, that is hopping trains to rob migratory workers of their earnings. There are pieces about all of these in the book as well as insights into how carny conmen, Prohibition-era saloon keepers and other hustlers operated. Yeggs, political activists and migratory workers regularly found themselves arrested in the course of their work and travels so depictions and exposes of life in jails and prisons across America are another recurring theme.

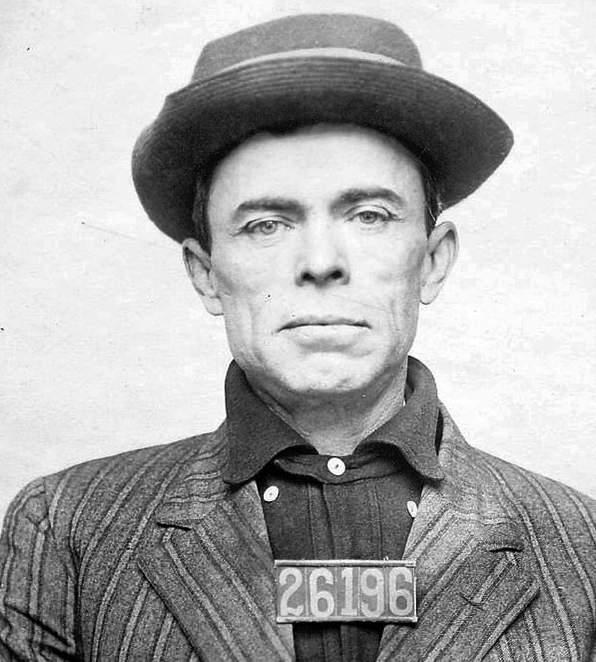

Some of the works that deal with these topics were written in a comic or adventure story style, but many employ a tough realism that foreshadows and echoes that of classic hardboiled pulp and true crime reportage. Jim Tully’s story ‘Thieves and Vagabonds’, which involves a group of hoboes stuck in a watch-house amidst sub-zero weather has a definite noir feel. Carl Panzram’s recollections of the abuse he endured as a teenage hobo and inmate, and the way it set him up for a lifetime of murder and mayhem, is about as unsentimental and brutal as it gets.

Where there any gaps in terms of subject matter or groups you were keen to represent in this book or couldn’t find material for?

While most hoboes were American born Caucasian males up to ten percent of them, depending on the period and region, were African-American. There were also a large number of women on the road, particularly during the Depression years. Because of the nature of the times these people not only faced greater hazards than other hoboes, but were also largely ignored by publishers and editors.

I was able to find a few pieces from male African-American writers, such as William Attaway who wrote a harrowing account of rail riding in his novel Blood on the Forge that’s quite at odds with the more common tales that emphasize the adventure alongside the risks. For the most part African-American perspectives came via music as blues and other musicians regularly got around by hopping trains. As a result I’ve included a number of lyrics from artists such as Blind Willie McTell, Bumble Bee Slim, Tampa Red and Peetie ‘The Devil’s Son-In-Law’ Wheatstraw.

Although Boxcar Bertha’s 1937 autobiography was supposedly by a female hobo it was actually written by anarchist and ‘slum doctor’ Ben Reitman, who was a major figure in Chicago’s Hobo College. He later claimed to have combined a variety of experiences he’d heard from women into a single narrative. His book, and other articles and works by men, number amongst the few that discuss female hoboes so an extract is included. I’ve also included a first person account of life on the road that was given to a sociologist by a woman in the early 1930s and an extract from Barbara Starke’s 1931 memoir which covers the rise of hitch hiking.

One area which I particularly would have liked to have included more about is the lives of gay, lesbian, transgender and bisexual hoboes. The subject of sexuality in any form is generally skirted over in the literature of the time. Latter day studies of crime records, oral histories and other sources indicate that there was a lot of same-sex activity going on between consenting adults, and that hobohemia provided a place where such desires were far more tolerated, if not embraced, than elsewhere. Unfortunately I wasn’t able to source any accounts from such hoboes that were produced at the time, although there is some coverage, mainly negative, by others and hints in songs.

This interview originally appeared on Retreats From Oblivion: The Journal of NoirCon.

On the Fly! Hobo Literature & Songs, 1879-1941 is out now through PM Press.