Today I’m celebrating Noirvember with a terrific guest post by my friend Dean Brandum, film scholar and the man behind the wonderful site, Technicolour Yawn: Melbourne cinemas of the happening years: 1960 – 84. Dean looks at the myths and realities around the exhibition of classical film noir in forties and fifties Melbourne. Film noir is often seen as mainly comprising B-movies that would never have graced the screens of reputable Melbourne cinemas. But, as Dean makes clear, for the most part this was not the case.

“You could always find me in the theatre round the corner. People like me liked our pictures dark and mysterious. Most were B-movies made on the cheap, others were classy models with A-talent, but they all had one thing in common, they lived on the edge. They told stories about life on the streets, shady characters, crooked cops, twisted love and bad luck. The French invented a name for these pictures – Film Noir.”

“You could always find me in the theatre round the corner. People like me liked our pictures dark and mysterious. Most were B-movies made on the cheap, others were classy models with A-talent, but they all had one thing in common, they lived on the edge. They told stories about life on the streets, shady characters, crooked cops, twisted love and bad luck. The French invented a name for these pictures – Film Noir.”

Richard Widmark narrating The American Cinema’s episode ‘Film Noir’

Whilst this TV overview of film noir was an excellent production and was immeasurably aided by the gravitas of the (then otherwise retired) voice of Richard Widmark’s narration, his opening introduction has always rankled with me, for it perpetuates a myth about film noir, one which has been developed to be shoe-horned into a narrative – that film noir was not a mainstream commodity.

Let’s unpack Widmark’s quote (no doubt written by somebody else). He would be found watching these films “in a theatre round the corner”: In other words they did not screen in your typical popular venues and instead were relegated to the dark and dingy second run or grindhouse venues. That “most were B-movies, made on the cheap, others were classy models with A-talent”. This implies that that the majority of these films were to be found propping up ‘quality’ Hollywood productions and discovered only by those who were prepared to sit through a B-film first half in order to enjoy the fruits of the advertised flick. That somehow, the ethos of film noir was smuggled in theatres under the guise of innocuous second features.

Now certainly there were many B-films which were of the crime genre with a number of them featuring the usual tropes of the time, usually involving a girl, a gun and a sleuth solving a convoluted crime in 60-odd entertainingly efficient minutes. But few, if any of these films were noir.

Now certainly there were many B-films which were of the crime genre with a number of them featuring the usual tropes of the time, usually involving a girl, a gun and a sleuth solving a convoluted crime in 60-odd entertainingly efficient minutes. But few, if any of these films were noir.

The vast majority of films noir were not relegated to bottom-of-the-bill status and many of them received releases in prestige theatres, so let’s nip this myth in the bud right now, okay? A form of collective nostalgia has evolved around this aspect of noir and it is time to put an end to it. And in this piece I’m going to us my (and Andrew’s) city of Melbourne as an example.

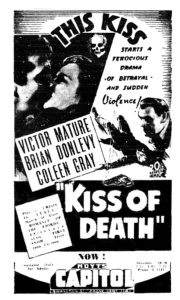

For starters, let’s start on the great Richard Widmark himself. The film that made him a star was indeed a noir, Henry Hathaway’s terrific Kiss of Death (1947). In this film Widmark is most memorable as a psychopath who pushes as wheelchair-bound woman down the stairs to her death. A B-flick? No. Playing around the corner? Not really, unless you count Melbourne’s 2,115-seat Capitol Theatre (located on Swanston Street, the city’s main thoroughfare) as ‘around the corner’. These things are arguable, but at the time (November 1948) The Capitol remained one of the city’s largest and most prestigious theatres and when Kiss of Death opened, it was strong enough a title to play without feature support and to last for a two week season in the theatre (a strong performance in those busy and prolific times).

For starters, let’s start on the great Richard Widmark himself. The film that made him a star was indeed a noir, Henry Hathaway’s terrific Kiss of Death (1947). In this film Widmark is most memorable as a psychopath who pushes as wheelchair-bound woman down the stairs to her death. A B-flick? No. Playing around the corner? Not really, unless you count Melbourne’s 2,115-seat Capitol Theatre (located on Swanston Street, the city’s main thoroughfare) as ‘around the corner’. These things are arguable, but at the time (November 1948) The Capitol remained one of the city’s largest and most prestigious theatres and when Kiss of Death opened, it was strong enough a title to play without feature support and to last for a two week season in the theatre (a strong performance in those busy and prolific times).

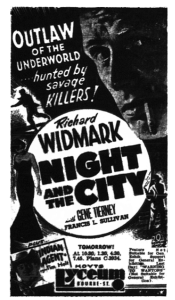

Let’s move along a little, up to January 1951 when Widmark is top-lining Jules Dassin’s Night and the City (1950) a London-set noir in which small-time hustler Widmark attempts to muscle in on the wrestling racket. To a degree Widmark is right in that this film played “round the corner” in that it opened at the Lyceum, a 1386-seat theatre that had fallen into disrepair by this stage and although it was part of the Hoyts chain (one of the country’s major operators) it was known as ‘the bughouse’ by regular patrons who enjoyed a mix of male-attuned genre flicks including noirs, other crime, westerns and horror features until its makeover in 1963 as a prestige house for the company and with a renaming to  The Cleopatra Theatre to house the engagement of the Liz and Dick epic (after that film close its name was changed to The Paris and it lingered through until 1970 when it finally closed and was met by the demolition ball shortly afterwards). Night and the City ran for three weeks at the Lyceum which was an excellent result for a venue that was used to weekly changeovers and it screened as the main feature, with the Tim Holt western Indian Agent as support.

The Cleopatra Theatre to house the engagement of the Liz and Dick epic (after that film close its name was changed to The Paris and it lingered through until 1970 when it finally closed and was met by the demolition ball shortly afterwards). Night and the City ran for three weeks at the Lyceum which was an excellent result for a venue that was used to weekly changeovers and it screened as the main feature, with the Tim Holt western Indian Agent as support.

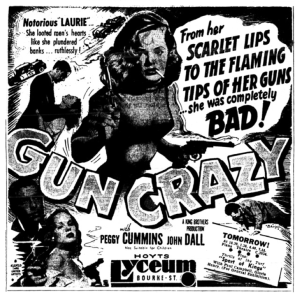

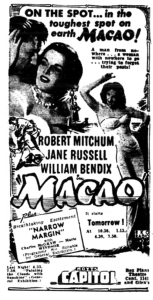

The Lyceum became the home to many noirs on their first release, with its distribution supply at the time dictated by its leasing company, Hoyts who carried the films of Fox, RKO and (some) Warner Bros titles (also a number of Universal features from previous agreements). Hoyts had six venues in the central business district at the time with The Regent being its most opulent and prestigious, Slightly behind was The Plaza (located underneath the Regent) and between them these two took the best their Hollywood suppliers would offer. The Capitol took the next most attractive (mostly of a genre-based variety including the noirs High Sierra, The Maltese Falcon, Laura, In A Lonely Place and Pick-Up on South Street) and The Athenaeum concentrated on British product (including a number of noirs but that is a story for another day). The Regent and Plaza were located opposite the Athenaeum in Collins Street, the centre of ‘quality’ filmgoing in Melbourne, with MGM’s St. James Theatre located further up the same street. A block away were Hoyts’ Lyceum and Esquire Theatres, each offering less-prestigious fare. Among (many) other noirs to play at the Lyceum were Crossfire, The Set-Up, D.O.A and The City The Never Sleeps. The Esquire screened Out of the Past, The Blue Gardenia, Cry of the City, Panic in the Streets, The Prowler and On Dangerous Ground. All of these were first-run product and they were all top-billed with generous advertising. Now it should be said that each of these films had, as Widmark would say “A-Talent” but what of those noirs with less lustrous names to exploit the film? Take the case of Joseph H. Lewis’s insane Gun Crazy (1950). Forget the star-power as all the Lyceum needed was a girl and a gun and it was straight to the top of the bill as this fabulous ad shows.

Similarly, let’s go back to what many believe was the very first example of noir. A brief (but crucial) Peter Lorre appearance was about the only aspect on which this film could be sold so you could assume it would be relegated to the support program on its first run. But not at the Lyceum.

Similarly, let’s go back to what many believe was the very first example of noir. A brief (but crucial) Peter Lorre appearance was about the only aspect on which this film could be sold so you could assume it would be relegated to the support program on its first run. But not at the Lyceum.

Okay, so the Lyceum played second features at the top of the bill, but it was a bughouse so we can make allowances. Surely a major, prestigious venue would not have been caught dead giving prominence to such flicks? Well, it is a somewhat forgotten fact that during the Second World War the Princess Theatre in Spring Street converted to a policy of film exhibition instead of its popular live entertainment (carrying a range of mostly Universal and Paramount product). This grand and opulent theatre was the first port of call for Double Indemnity, The Killers and The Blue Dahlia. Once again, here’s the A-talent at work. But in 1945, for a week before it opened, “The Phantom Lady Is Coming!” ran across the movie listings pages of Melbourne’s newspapers. Franchot Tone and Ella Raines were hardly huge names (even back then), yet The Princess gave this film a huge boost.

At the top of the hierarchy of theatres in Melbourne, the most prestigious in the early 1940s was Hoyts Regent in Collins Street and until it fell into disrepair and decline years later, the likes of a ‘crime melodrama’ would never have sullied its projectors, certainly not as a main feature. Thus it was extremely rare to find a noir unspool at the Regent, unless it was within the guise of a ‘woman’s picture’ such as the Joan Crawford starrer, Possessed. However The Glass Key did sneak into Regent, albeit as a second feature to a Bob Hope comedy. How the Regent’s dignified audience would have found the sadomasochistic and perhaps homoerotic violence of the Ladd-Lake-Bendix noir is difficult to say, but I’m certain it would have been a smash hit had it first screened ‘round the corner’ at either the Lyceum or the Esquire.

The other major theatre time was Union Theatres (later to be known as Greater Union and until 1950 (when it was gutted by fire) their Liberty Theatre in Bourke Street (yes, that hub of depravity!) was its version of The Lyceum – an action house – for weekly changeovers of genre flicks geared to a male audience. This Gun For Hire, The Black Angel, Moonrise and Criss-Cross all had top-billed first runs at the Liberty. The company rebuilt a venue on the site – The Odeon – but it was a far classier affair with a strong British bent to its screening policy. Instead, the noirs available to Greater Union in the 1950s (mostly Paramount, Universal and Columbia) were shared between the State (later to be known as the Forum twin) and the Majestic next door on Flinders Street. It was the former that took the more prestigious offerings including Sorry Wrong Number, Sunset Boulevard and Naked City leaving the Majestic to serve up Scarlet Street, The Big Clock and The Big Heat.

As the distributor of Columbia’s product Union had the rights to Gilda, but for Christmas of 1946, with the Bob Hope comedy Monsieur Beaucaire doing good business at the State and the locally produced epic The Overlanders a smash hit at The Majestic, the decision was made to send Rita and Glenn to The Savoy. A nominally independent Russell Street venue that enjoyed spillover from over-burdened suppliers, the Savoy later enjoyed success as the city’s prime arthouse theatre. Gilda was a smash for the Savoy, screening for nine weeks.

As the distributor of Columbia’s product Union had the rights to Gilda, but for Christmas of 1946, with the Bob Hope comedy Monsieur Beaucaire doing good business at the State and the locally produced epic The Overlanders a smash hit at The Majestic, the decision was made to send Rita and Glenn to The Savoy. A nominally independent Russell Street venue that enjoyed spillover from over-burdened suppliers, the Savoy later enjoyed success as the city’s prime arthouse theatre. Gilda was a smash for the Savoy, screening for nine weeks.

For the purposes of this piece I surveyed the first run particulars of 80 noirs in Melbourne and of these, only nine opened as second features. These included Tension and Border Incident (both used as supports at MGM’s St. James theatre) the aforementioned The Glass Key, They Live By Night (under the title The Twisted Road and I Wouldn’t be in Your Shoes propping up the popular Portrait of Jennie at the Majestic. Generally attempts were made by distributors to mix-up the genres in first run double-feature programming, making this double-noir at the Capitol a rare thing

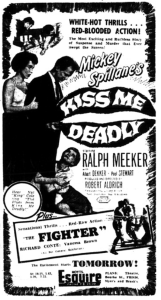

As the classical noir period faded in the mid-1950s television arrived in Melbourne and although it took a few years to make its impact felt, it would result in swathes of suburban venues being closed and city theatre operators re-thinking their programming policies. Out went the B-films and soon weekly changeovers of genre double features would also be discarded. On September 27th 1956 GTV9 began its first Melbourne TV transmission. The following day Robert Aldrich’s incendiary Kiss Me Deadly opened at the Esquire Theatre. The end was nigh for classical noir and for this type of theatrical programming. But with this film it went out with a blast and in a mainstream cinema, and as a top-billed item. They way they almost always were in Melbourne. The collective nostalgia of back street cinemas and noirs hidden away at the bottom of the bill were, in this city at least, a myth. But the actual nostalgia is just as rich and just as rewarding.

Very interesting. Human beings have a tendency to remember the past in a way that conforms to the way they want to perceive themselves now. Thus, we always remember our childhoods as being more idyllic and simple than was really the case. In the US, baseball pundits call the 1950’s “The Golden Era.” But a cursory review of attendance figures shows just the opposite. Ditto for film buffs. The words “film noir” conjure up notions of danger, violence, and fatalism all wrapped up on a downhill spiral on a grimy road to hell. That life is much more enjoyable being lived through one’s imagination than actually having to push someone off the back of a train while trying to hack out a living selling life insurance. So we imagine reality in a way that fits present day perceptions. There is an old saying: the easiest person to lie to is yourself.

Nicely put, Dennis.

Terrific article, Dean. I find it appropriate that you take your myth-busting cue from Richard Widmark, who played such ghastly characters (who’d push a woman in a wheelchair down the stairs?!), yet was by all accounts a very decent guy.

Thanks Dennis and Angela!

Ang, I always have a sweet spot for Widmark as he bore quite a resemblance to my father. Dad’s best mate happened to look a fair bit like Richard Todd and thus they were known as “The two Dicks”. Well, dad tells me it was for looking like famous Richards….maybe it was just because they were somewhat more disreputable characters.

I remember him in Madigan. Was first a movie and then a one hour police drama. Widmark played a tough talking New York City detective who reminded me of Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle. Henry Fonda also starred in the movie.