In her latest book, This House of Grief, Helen Garner examines the case of Robert Farquharson, who on Father’s Day 2005 drove his car into a dam off the Princes Highway near Geelong, drowning his three young sons. It is among a number of recent works that demonstrate how true crime writing has changed over the last few years.

Others are Anne Krien’s Night Games: Sex Power and Sport, which won the 2014 Sisters in Crime Davitt award for best true crime book, and Robin De Crespigny’s The People Smuggler, ostensibly a non fiction story about the experience of an Iraqi asylum seeker, which took the 2013 Ned Kelly crime writing award for best non-fiction. Matthew Condon’s Jacks and Jokers is another example. The second instalment of a trilogy about police corruption in Queensland from the sixties to the Fitzgerald Inquiry in 1987, it has the feel of an ambitious alternative social history rather than a piece of true crime writing.

“In terms of definition,” says veteran true crime writer Lindsay Simpson, “true crime is a literary rendition of a particular crime which pays homage to veracity by researching the crime across multiple sources including interviews and primary source documents while at the same time engaging the reader through its narrative.”

Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966), his investigation into the 1959 murder of a Kansas farmer Herbert Clutter, his wife and two of their four children, is often credited with pioneering the more literary end of the true crime genre. Despite allegations Capote took liberties with the story the book has had huge critical impact. It took Capote five years to research and write.

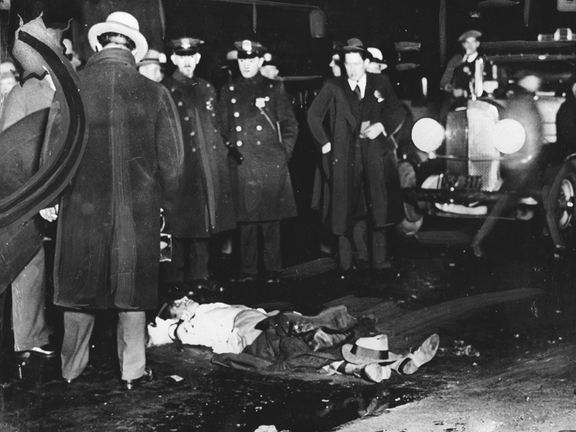

At the other end of the spectrum are more lowbrow and sensationalist offerings. These hark back to the time when true crime was the preserve of lurid magazines and pulp books. Written and turned around quickly, these books often feel cobbled together from newspaper clippings or existing interviews and are designed to maximise public’s fascination with a particular crime or series of crimes.

This House of Grief arguably has a foot in both heritages. Farquharson’s crime caused widespread shock and revulsion and gripped public attention. But Garner’s telling has won praise for the literary quality of the writing and its nuanced observations. Add to this a dash of good old-fashioned courtroom drama. “You won’t read a better description of the rarefied air of an appeal court,” wrote the Saturday Age’s Cameron Woodhead in a recent review. “The twists and turns of this true crime story are in Garner’s hands, more engrossing and dramatic than any thriller.”

“I think good true crime is about profound realities like crime and punishment, justice, and ultimately resilience for those left shattered in its wake,” says Melbourne true crime writer Vikki Petraitis. “Is [a book] true crime simply because there is a crime in it? Mostly, these questions are answered by the publisher and which shelf the book appears on. What I do know is that good true crime should have a wider application and make people think long and hard not only about the crime, but its broader implications. When Phil Cleary wrote about the provocation law (which allowed men an ‘excuse’ in the killing of their partners) it helped push for a change in the law.”

In addition to good writing, books like Night Games and The People Smuggler also deal with issues not usually thought of as being in the remit of traditional true crime, the finer points of sexual consent or issues around asylum seekers and people smuggling, ‘crimes’ in which the guilty party and the nature of their crime are unclear.

“My sense is that there are still quick hit and run books and more serious and thoughtful ‘literary’ works, as there have always been,” says Wollongong University Professor and co-convenor of the Sisters in Crime, Sue Turnball.

What is undeniable is that the publishing environment for true crime has changed. As Simpson recalls: “When Brothers in Arms [the book she wrote with Sandra Harvey about the about the Milperra bikie massacre] was published in 1989, there was no true crime section and we were told that many bookshops were confused as to whether to sell it as fiction or non fiction.” This confusion, she believes, resulted largely from the fact there were so few books like it. “In the past two decades, true crime writing has grown steadily as a genre in Australia, rivalling crime fiction.”

Why is true crime in its various guises so popular?

“Firstly, the age-old and worldwide fascination for deviance,” says Perth crime writer David Whish Wilson, whose 2010 crime novel, Line of Sight, is based on real events surrounding the unsolved murder in the seventies of South Perth brothel owner Shirley Finn. “Secondly, plain old marketing. As a popular genre the books seem to be everywhere, especially at airports. Finally, and most importantly, while the subject matter is non-fictional, a good true crime writer uses the skills of creative non-fiction as a means to take disparate facts and events and bring the whole thing to life by way of effective characterisation, strong visual language, and an ability to order the various facts and events in the best possible way.”

One factor that could be driving the new breed of true crime books is the increasingly diverse backgrounds of those writing them. While Simpson comes from a strong investigative journalism background, Garner is a novelist and screenwriter and de Crespigny a filmmaker. John Safran, author of another acclaimed true crime work, Murder in Mississippi, was a filmmaker, radio broadcaster and cultural commentator.

Connected with this are the increased resources available to those writing true crime. Writers can now get access post mortem reports on line. Pictures of the accused, their victims and their families are often splashed across the media. Transcripts of investigations, financial records, material that used to be the preserve of working journalists, are now more freely available. “What this will do to the genre is yet to be evaluated,” maintains Simpson. “It detracts from the old fashioned ‘shoe leather’ approach of getting out of the office and doing your research.”

“Journalism is still the best training ground for the true crime writer,” according to Melbourne true crime author, Adam Shand, currently working on a book about the life of criminal identity Mark Chopper Read. “You start off with whoever will talk to you. That’s the bottom line. After that it’s really a question about journalistic method. If you have worked in a media environment you get used to the idea that you have to have multiple sources. Whatever you are told you have to try and cross reference with a document or some other source.”

“A lot of true crime writing really is simply basic journalistic craft,” agrees Condon, who has interviewed over a thousand people for the first two books in his planned trilogy. “Go out and find other people and try and verify incidents from different angles.”

Not that subjectivity doesn’t have a part to play in good true crime writing. Garner often writes about how the events she is covering have impacted on her. Others, like Chloe Hooper, author of The Tall Man, choose to write from a first person narrative.

“True-crime writers take a side and we use very persuasive language to build our cases,” notes Petraitis. “When I wrote about serial killer Paul Denyer in The Frankston Murders (1995) I was never going to be sympathetic to him. I offered him the opportunity to talk to me, but was secretly relieved when he refused. I didn’t want to accommodate whatever excuses he would invariably come up with for killing three young women.”

Simpson’s latest book, Where Is Daniel? is about the disappearance of Daniel Morcombe while waiting for a bus near his Sunshine Coast home in September 2003. Written with his parents, Bruce and Denise, Simpson was not only deeply affected by the story, she became a small player in the saga by echoing their criticisms of aspects of the ten year police investigation, the largest in Australian history.

Condon briefly became a media participant in his own story when disgraced former Queensland police commissioner Terry Lewis, who was working with Condon on the story, severed all ties soon after the May 2014 release Jacks and Jokers, and demanded the return of thousands of confidential files and documents.

Condon has also found himself becoming a magnet for stories, tip-offs and documents from people across Queensland who, up until the publication of the first book, Three Crooked Kings in 2013, were too scared to come forward. “A lot of people [have] felt there was just enough passage of time to for them to think, ‘what the hell, I’ll tell you what happened.’

This article originally appeared on the Wheeler Centre site here. Some of the quotes were drawn from the panel session, ‘True Crime Truths’, which took place August 16 as part of the National Non-Fiction Festival.