What I love about the canon of cinema known as film noir is just when you think you’ve seen the all important films, along comes something and blows you away.

What I love about the canon of cinema known as film noir is just when you think you’ve seen the all important films, along comes something and blows you away.

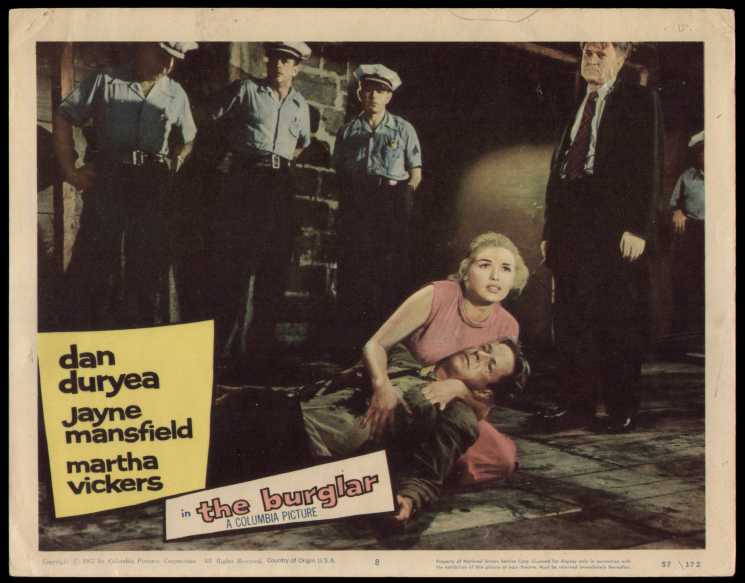

Thus was the case recently when I watched the 1957 film The Burglar, based on the book by one of the doyens of classic noir fiction, David Goodis, who also wrote the screenplay.

It begins with a cinema newsreel story titled “Estate sold to spiritualist cult in strange bargain”. The breathless voiceover tells cinemagoers how a millionaire called Bartram Jonesworth has died and left his estate, including a mansion and an emerald necklace, to an aging spiritualist called Sister Sarah.

In the cinema audience is career burglar Nat Harbin (long time TV and movie actor, Dan Duryea). So keen is he to get to work on what could be the score of a lifetime, he doesn’t stay for the feature, he bolts outside and starts thinking about how they can steal the necklace.

He gets his stepsister, Gladden (Jayne Mansfield) to case the mansion under the pretences of visiting to make a donation to Sister Sarah’s work. Gladden informs Harbin and his associates, Baylock and Dohmer, the necklace is kept in a safe in Sister Sarah’s bedroom. The best time to make a move is the fifteen-minute window at eleven o’clock each night during which the spiritualist always watches her favourite news show.

Harbin and his crew are almost busted mid-job by a couple of cops who get suspicious when they find Harbin’s car outside the mansion. Warned about the police by his associates, Harbin manages to talk his way out of being rousted, get back into Sister Sarah’s bedroom, crack the safe and lift the necklace, before the spiritualist retires for the night.

The gang drive back to their dingy apartment with the necklace. But, as is the case with any good heist film, things begin to go badly wrong. The gang start bickering about what to do with the necklace. Baylock, the most tightly wound of the three men, wants to fence it straight away, get his share of the money and blow town for South America. But Harbin wants to wait until the heat around the job has died down.

“Why the slow motion?” demands Baylock. “What are you waiting for?”

“A drop in the temperature,” answers Harbin. “You think that’s hot? It’s hotter out there. Boiling hot. The law, Baylock, the local authorities, the blue boys. What do you think they’re doing right now, sleeping?”

The cops are indeed on the case. So is something else whose car we see pulling up outside the gang’s apartment, checking them out.

The tension builds. Baylock wont’ stop nagging about the money Gladden is angry because Dohmer is always eyeing her off.

To cool things down Harbion sends Gladden to Atlantic City. No sooner does she arrive than she starts a romance with Charlie, who happens to be one of the cops who found Harbin’s car on the night of the burglary and who has been stalking the gang ever since, waiting for an opportunity to steal the necklace. Double cross quickly piles up on double cross, people start dying, leading up the final confrontation in the most noir of settings, an amusement arcade.

Barely constrained, sometimes incestuous or oedipal sexual desire is a constant in much of Goodis’s work and The Burglar is no exception.

Gladden is the daughter of a professional burglar who took the young Harbin in after he escaped from a boy’s home. The man looked after Harbin and taught him his trade. His last wish, as he lay dying with several police bullets in his chest, was for Harbin to look after Gladden. The pledge is strangling Harbin. He desires his stepsister and she him, and it’s all he can do to keep their sexual heat in check and honour the burglar’s dying words.

The presence of Mansfield in the role of Gladden only adds combustion to the fire. Billed as the ‘working man’s Marilyn Munroe’. The Burglar was one of her early roles to cash in on 20th Century Fox Studio’s attempts to turn her into Hollywood sex symbol, after she’d received considerable attention in Pete Kelly’s Blues, also made in 1955.

The Burglar was Goodis’s ninth novel and one of his many works adapted for the small and large screen. It was also one of several screenplays he wrote, many of which reportedly never saw the light of day. The Burglar was remade as a Euro caper film in 1971, starring Jean-Paul Belmondo and Omar Sharif.

The Burglar got me thinking about the difference between film noir of the late forties and early fifties, and noir movies of the late fifties and early sixties.

Noir cinema has always been about alienation, paranoia and lack of control. But the films from the late fifties and early sixties have an intensity about them. Think Kiss Me Deadly (1955), Cop Hater and Touch of Evil (1958) Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) Blast of Silence (1961), Sam Fuller’s Underworld USA (1961) and his wonderfully transgressive 1964 movie, The Naked Kiss, and you’ll get an idea what I mean.The pacing and plot of these films feels faster and more tabloid. The settings are sleazier and the often unrequited sexual desire closer to the surface.

The immediate era after World War was marked by fluidity and mobility, due to the fact that the war had taken a wrecking ball to social structures and gender relations. By the mid-fifties the state and its dominant social relations had regrouped and were on the counterattack in the form of fear of communism and strict moral and political conformity.

The pressure from this weighs heavily on the characters in late fifties film noir. Like Harbin, they feel like they are almost going to burst from the accumulated sexual and economic anxiety.

Hi , great bit of writing and well thought out dissection of fil noir timeline. I really enjoy this site and come away thinking how lucky all your readers are. Keep up the good work, sincerely, Andy

Andy,

Thanks so much for the feedback. It’s great to know people are reading the site and appreciate what I am writing.

Andrew

I’m a big Goodis fan. Nicely done, Andrew. Time for me to revisit this film.

And book. ~ Mark

Mark,

I haven’t read the book (but I assume it’s good). As I hope I’ve indicated in the piece, the movie is definitely worth checking out.

Andrew

Pingback: May 2014: Classic crime in the blogosphere | Past Offences Classic Crime Fiction

I think The Burglar is the saddest book I have ever read. Have never been able to bring myself to see the film. Goodis is the Master Of Misery, the Dean of Desperation. I suspect, as is true in most cases, the film is much inferior to Goodis’ book – I just recently watched Nightfall and the director Jacques Tournier butchered the book. It seemed to me the only connection of the film to the book was its title and the fact of some missing money. Sadly most noir novels have suffered from the directors ego and their strange conviction they can spin a better story than a great writer. Then again it was always thus. Goodis was a literary genius and if he had not been regarded as a “crime writer” would have been up there with Hemingway and Dickens.