A couple of years ago I had a lengthy exchange on social media with a British crime writer on the subject of what was the best crime film to come out of the UK, Get Carter (1971) or The Long Good Friday, released in 1980.

I have to fess up that at the time I took exception to his claim Get Carter had aged badly and The Long Good Friday was the superior piece of cinema, but he was right and I was wrong. I was reminded about this last week, when I heard the star of the Long Good Friday, Bob Hoskins, had died at the age of 71.

Get Carter and The Long Good Friday are both good films, especially in comparison to the slew of movies riffing on London’s underworld past that followed in the wake of Guy Richie’s rather middling effort, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels.

The Long Good Friday is the story of working class gangster made good, Harold Shand, whose criminal empire starts to unravel, for reasons he is totally unclear about, over a bank holiday long weekend.

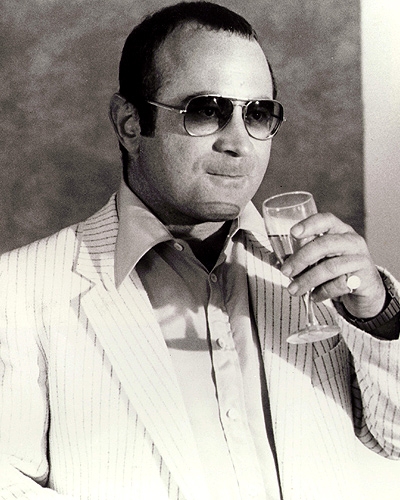

Hoskins owns this film from the first moment we see him, walking down a concourse in Heathrow Airport, having just returned from business overseas, the eighties soundtrack pounding in the background. It’s a scene that reminds me of Lee Marvin’s entrance in John Boorman’s 1967 movie, Point Blank.

Shand embodies many of the clichés we have come to associate with British gangster cinema. He’s a working class bruiser who has fought his way to the top of the pile using brutality that is only hinted at in the film. He has an array of colourful underlings, bent coppers and corrupt local government officials on his payroll. He also has an aging, very religious mother.

Like countless cinema gangsters before and after him, he’s trying to take his ‘corporation’ legitimate. He has a plan to develop disused industrial waterfront land that he wants to finance with the help of the Mafia, two representatives of whom arrive in London for the long weekend to nut out the details of the deal.

But just as everything appears to be going Shand’s way, his second in commend, Colin, is viciously murdered. The car used to ferry his mother to church is blown up and the driver killed. An unexploded bomb turns up at his casino and the pub where he intends to takes his Mafia guests to lunch, is destroyed by another bomb just as Shand and his guests pull up outside it.

Shand can’t understand who is behind the anarchy, which is jeopardising ten years of profitable gangland peace.

The Mafia representatives give him 24 hours to sort things out or the deal is off. Shand leans on every underworld contact he can think of, hard, to get the details of who is behind the mayhem. This leads to my favourite scene, where Shand has his men round up the heads of all the other ‘manors’ and hangs them upside down in a meat works, until someone confesses.

The reality is far more complex and dangerous. Unbeknownst to Shand, Colin was running funds for the Irish Republican Army. Worse, the IRA blame Colin, and hence Shand’s organisation, him for some money that has gone missing and several of their senior people who have been arrested by the British.

On one level, The Long Good Friday is similar to another film I reviewed on this site a few months ago, Villain (1971) starring Richard Burton. Vic Dakin, the gangster in Villain is a snarling rightwing, closet gay psychopath. Harold is also a Tory and, like Dakin, a racist, and his de facto response whenever the pressure gets too much, is to revert to violence.

But, unlike Dakin, Harold fancies himself a sophisticated businessman and international entrepreneur. Margaret Thatcher had swept to power a year earlier, legitimising Britain’s previously marginalised nouveau riche, people like Shand. Supporting him in his quest to become part of the ruling class is his smart, ambitious girlfriend, Victoria (a wonderful performance by a young Helen Mirren).

Like Thatcher, Shand is also a staunch nationalist. He looks down on his potential American partners, telling Victoria, “The Yanks love snobbery. They really feel they’ve arrived in England when the upper classes treat them like shit… Gives them a sense of history.” He also has enormous difficulties coming to grips with the fact that it is the IRA, not another criminal organisation, who has him in their sites. When the reality does eventually sink in, his ruling class disdain lulls him into a false sense of superiority. Instead of negotiating, he kills the two IRA men he makes contact with.

The folly of this only becomes apparent in the very final scene when the IRA whisks he and Victoria away in separate cars. Hoskin’s performance is masterful as his face transformed from anger to defiance to resignation to his inevitable fate.

The Long Good Friday was Hoskin’s breakout role and, along with Mona Lisa (1986), is my favourite of his performances.

I saw this years ago and should see it again. Thanks for reminding with this very detailed overview.

Pingback: Sexy Beast: the last good British gangster film | Pulp Curry

Pingback: My top 10 British gangster films | Pulp Curry