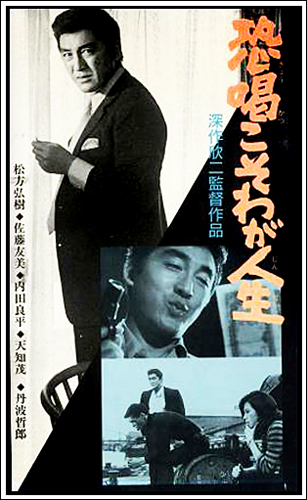

A couple of nights ago I finally got around to viewing a film that’s been on my must-watch pile of DVDs for ages, Kinji Fukasaku’s Blackmail Is My Life.

Regular Pulp Curry readers will know I have a bit of a thing for Fukasaku’s work, having previously reviewed two of his films on this site, Yakuza Graveyard (1976) and Street Mobster (1972).

Released in 1968, Blackmail is set in Tokyo at the beginning of the country’s economic boom. The story revolves around four young slackers who will do anything to avoid the trappings of mainstream middle class life. They are a tight knit group comprising former Yakuza, Seki, ex-boxer Zero, Tom Boy sex bomb Otoki, and their leader, Muraki.

Muraki may look like a bit of a fool with his hounds tooth jacket and permanent grin but he’s an expert in his chosen craft – blackmail. He’s also completely unafraid of anything. As he puts it: “The bigger and tougher they are the more reason to taker them down.”

Their targets are mostly “stupid arsed salary types”, low level starlets and businessmen who the gang secretly film committing adultery in seedy love hotels. But Muraki is keen to take things up a notch. His opportunity comes when he leans of the existence of the ‘Otaguro Memorandum’, a document that could bring down a corrupt high-level Japanese politician if it ever saw the light of day.

Needless to say, the powerful individual does not take kindly to being shaken down by a bunch of street punks.

As a voice over from Maruki says at one point in the film, “The prettier something looks on the outside, the more revolting it is on the inside”. It’s a perfect description of Japanese society in the sixties. While the country’s stellar economic growth and glittering consumer culture made the desperate poverty experience in the post-war Japan seem like a distant memory, much of this development was based on lies and political corruption.

Fukasaku came of age after World War Two and emerged from the hardscrabble Occupation years imbued with a deep cynicism and a mistrust of authority. The target of his ire in Blackmail was a real life corruption case in which senior member of the country’s Diet (parliament) was caught extorting fellow politicians and using the hush money to fund his campaigns. Although the media exposure of these activities created a political outcry, the politician concerned kept his post and went onto much bigger things.

Blackmail Is My Life contains all Fukasaku’s signature visual techniques, his extensive use of voice overs, usually across freeze framed images, the lack of linear story telling and his tendency to manically bounce between different points in the story, which gives the film a disjointed, alienated feel.

There’s a fantastic sixties sounding score and Fukasaku has a lot of fun with the technology used by the black mailer. His lurid use the images arising from the gang’s activities turn the viewers into voyeurs, a deliberate strategy which becomes particularly biting in the film’s final scene.

Pulp Curry readers interested a more detailed consideration of Japanese crime cinema should head over to the US-based website, Criminal Complex, where my Crime Factory colleague Cameron Ashley writes a great column, ‘The Nail that Sticks out’. This examines not just crime cinema but Japanese pulp and noir culture more generally. It’s a must for fans of Japanese crime film and fiction.