There’s been a bit of discussion in literary circles recently about whether enough is being done to maintain the public’s interest in the classics of Australian literature. To my surprise it’s a debate I’ve only been able to drum up half-hearted enthusiasm for.

There’s been a bit of discussion in literary circles recently about whether enough is being done to maintain the public’s interest in the classics of Australian literature. To my surprise it’s a debate I’ve only been able to drum up half-hearted enthusiasm for.

The catalyst was an article by Text Publisher Michael Heyward in late January, in which he criticised journalists, cultural commentators and university academics for failing to create an enduring tradition for appreciating and teaching Australian literature. He singled out universities in particular for the lack of courses about Australian writing.

Perhaps in response, the latest program put out by the Wheeler Centre includes a series of talks called Literature 101, in which contemporary writers talk about classic Australian texts.

You won’t get an argument from me about the importance of Australian literature in building our individual and collective sense of historical self. I also agree universities are failing to teach Australian literature, although I think the problem lies less in any wilful neglect on the part of academics than in the gradual privatisation of our higher education system. Persistent federal government underfunding has squeezed course diversity in favour of subjects that generate income, particularly full fee income. Australian literature is not Robinson Crusoe in this regard. Try studying ancient history or the language of a country that is not one of our major trading partners, and you’ll get the picture.

Nor do I want to spend much time quibbling about who should and shouldn’t be included in the canon of Australian literary greats. That’s always going to be a matter of taste. It’s worth noting that as part of Heyward’s efforts to revive interest in Australian literature, Text have announced a list of classic Australian books they intend to reprint cheaply. From a crime fiction perspective, it contains titles I think merit inclusion, such as the Peter Corris classic The Dying Trade, and others I don’t.

What annoys me off about the current debate is how it totally ignores Australia’s other literary heritage, the pulp fiction of the fifties, sixties and seventies, a period in which a huge amount of popular fiction was generated but which is almost completely unknown today.

What annoys me off about the current debate is how it totally ignores Australia’s other literary heritage, the pulp fiction of the fifties, sixties and seventies, a period in which a huge amount of popular fiction was generated but which is almost completely unknown today.

The local pulp fiction scene flourished in Australia for three decades after the government’s 1938 decision to levy foreign print publications. Local publishing houses sprang up to fill the void, releasing hundreds of novels a month, including Westerns, racing and boxing stories, science fiction and crime.

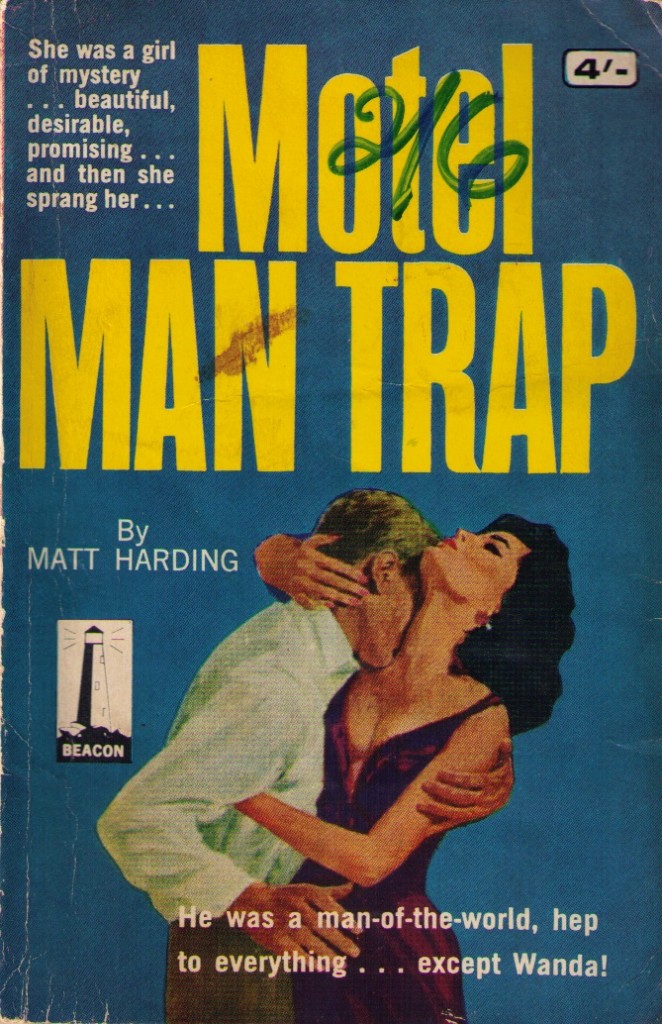

In the sixties and early seventies, major pulp publishers like Horwitz started offshoots like Scripts and Stag to distribute their racier titles. They also made an effort to supplement popular overseas titles with original work by local authors.

The result was a wave of true crime, movie tie-ins and exploitation fiction loosely dressed up as exposes of current social problems, youth rebellion, drug use and sexual promiscuity. Bikies were another popular subject. There was even and a string of pulp novels featuring the travails of women and servicemen in Japanese and German prisoner of war camps.

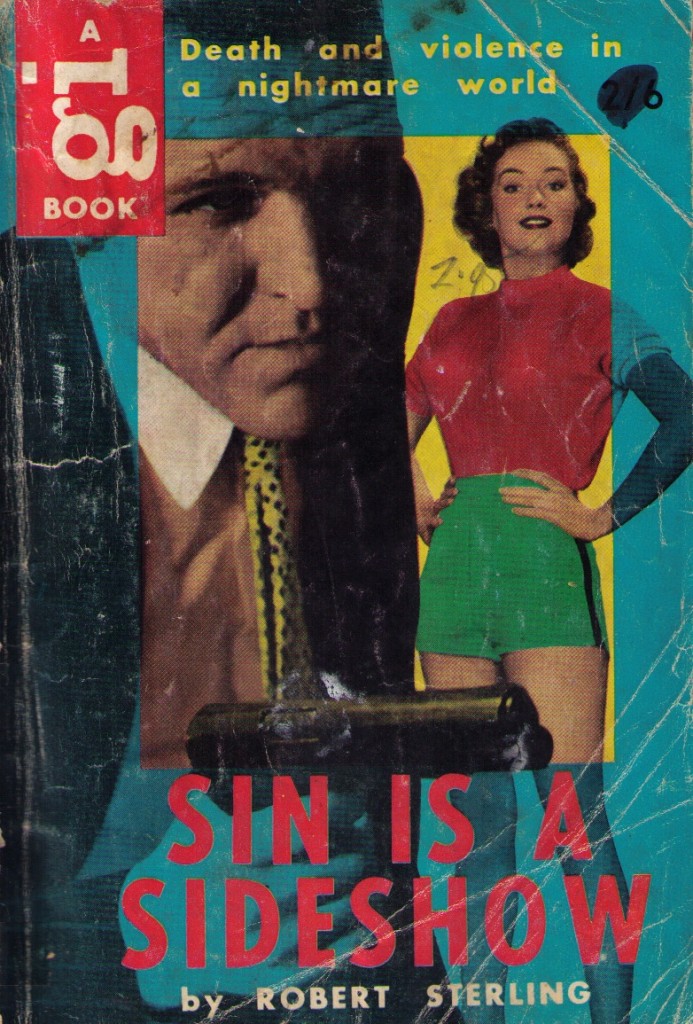

It was disposable fiction in every sense, printed on rough paper, featuring lurid cover art that often bore no connection to the story and sold cheaply at newsstands.

The authors worked fast to meet deadlines. Books were plotted, written and released in a month, for very little financial return. While a lot of the writing was crap some of it is pacey and showed surprising ingenuity in terms of plot and character.

What cannot be disputed was its popularity. Authors like Gordon Clive Bleeck, who wrote over 200 pulp novels while working full time for NSW Railroads, and Carter Brown, the alias of UK immigrant Alan G Yates, sold in the millions internationally. At the height of its popularity in the mid to late sixties, Horwitz and its offshoots published 16 a month, with initial print runs of 20,000 each.

Given all this, the speed and comprehensiveness with which Australia’s pulp publishing industry has been forgotten is staggering. Some, like Carter Brown and Marshall Grover may be remembered. Others, such as Stuart Hall, Jim Kent and John Slater are forgotten. Their books are becoming increasingly difficult to find. How they worked or where they got their ideas and inspiration, the bread and butter topics of today’s literary circuit, are unknown.

The only exceptions to this historical amnesia I am aware of is the research into the pulp writers of the forties and fifties by Queensland historian Toni Johnston Woods, and Melbourne resident John Harrison’s excellent book Hip Pocket Sleaze, which looks at pulp fiction publishing in the sixties and seventies.

No doubt a lot of people would scoff at the idea of placing pulp fiction alongside the classics of Australian literature as worthy being of preserved in our national imagination. I’m also aware, to put it politely, a lot of the pulp material will not be to everyone’s tastes. For me, pulp fiction is about the enjoyment of something fast and salacious, something I can’t help but think we’ve lost in the emphasis on capital ‘L’ literature.

No doubt a lot of people would scoff at the idea of placing pulp fiction alongside the classics of Australian literature as worthy being of preserved in our national imagination. I’m also aware, to put it politely, a lot of the pulp material will not be to everyone’s tastes. For me, pulp fiction is about the enjoyment of something fast and salacious, something I can’t help but think we’ve lost in the emphasis on capital ‘L’ literature.

But importantly they are part of our history. What does the pulp set in Kings Cross in the sixties say about then mainstream society’s fears of youth rebellion and changing sexual standards? And why were high-flying corporate executives behaving badly a staple of Australian pulp fiction in the sixties?

Heyward and others are right. Literature is one of the main ways through which we interpret national identity and it needs to be preserved. I applaud Text for putting their money where their mouth is and making available some of the classics of Australian literature.

But let’s all be clear, we’re only telling half the story.

Australia’s lost pulp heritage needs to be saved and you’re just the man to do it.

Fascinating post. I know my dad had some of these books on his bookshelf – I recognise the tyoe if lurid cover – and I’d forgotten all about them until now.

With ebooks, if someone has the time and inclination to scan and upload a sampling of these old books, maybe they will be preserved? They’ll be a fascinating additional resource to our multiple cultural histories as well as contribute to our understanding of our commercial writing heritage.

Elizabeth,

Thanks for stopping by. I agree with that these books could contribute a lot to our understanding of commercial writing. If you have a look at some of the previous posts I’ve done on the site, you’ll see that in my own very small way I’ve started to catalogue some of Australia’s pulp fiction heritage. Myself and the other editors at Crime Factory have also talked about doing electronic re-prints of some of these titles. We’ve just got to find the time to sort out rights, etc.

Andrew

Great post Andrew – pulp doesn’t equate to forgettable…

Dave,

Thanks. Always a pleasure having a comment from you. Look forward to seeing in a few weeks time.

Andrew

Good article Andrew.

Thanks, Iain. I think you’re one of my subscribers. I am always fascinated to know who subscribes to Pulp Curry and whether they actually read what I write. Glad you enjoyed the post and look forward to having you stop by again some time.

Andrew

And a mission well worth pursuing – good on you for taking up the cause (and reminding the rest of us about the necessity). Great article.

Hi Andrew, my knowledge of Oz Pulp is scant. Learnt loads here. Great post.

As my parents and grandparents have sold houses over the years I’ve helped cart of boxes and boxes of local pulp off to op shops and the tip. Didn’t think much about it – my tastes at the time didn’t lead me to bother flicking passed the racey covers. It does shit me that the literature of my family and their communities will be forgotten more or less. Good post.

Thanks Toby. Appreciated your feedback.

Andrew, I read your first post at 6 yesterday morning and I wanted to comment straight up. I imagined you in a flurry of sustained brilliance churning out a missive in the same fashion as the writers you so well supported. Keep up the great work. I wish I was writing so freely.