One thing I love about the canon of movies known as film noir is how I’m always finding something new. Sure, there are the classics and masterpieces everyone talks about. But every now and again you unearth a gem you didn’t know would be so good.

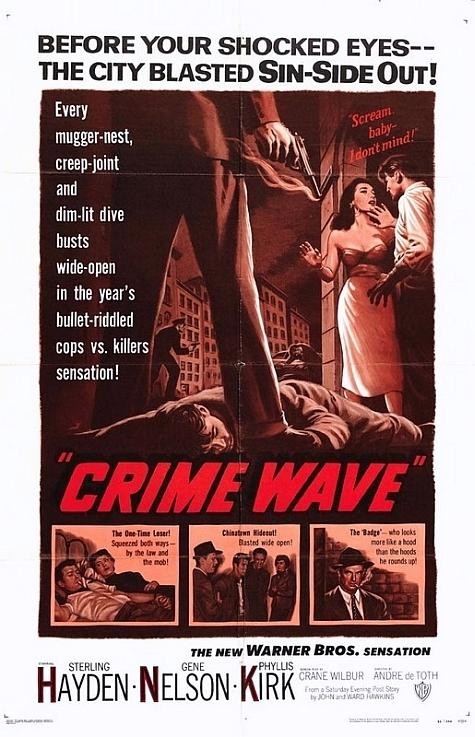

Like, for example, the 1954 Andre de Toth noir, Crime Wave, which I watched last night.

A trio of escaped cons knock over a gas station, killing a cop in the process. A full scale police manhunt ensures complete with what then must have seemed like the full array of hi-tech police gadgetry.

One of the cons is wounded during the hold up and left to fend for him self. The other two need a place to hide. They visit the home of another ex-con Steve Lacey and his pretty young wife, Ellen.

Steve wants to go straight, but the escaped cons have other ideas. The gas station is the latest of a string of chump change robberies they’ve pulled up and down the Californian coast. They need a major score to get enough money to get out of town for good.

They plan to rob a bank and want Steve as their wheelman. The ex-cons team up with other criminals, one of who takes Ellen hostage, to ensure Steve’s cooperation.

Crime Wave is a solid noir. The script is good. The action is gritty and realistic, no doubt due to de Toth who had a rep for realistically depicting violence in his films (his 1969 effort, Play Dirty, with Michael Caine, is for my money one of the best of the crop of anti-war war films of the late sixties).

Several other aspects of this film are worth mentioning.

It’s got a heist and an alcoholic ex-doctor who now works as a vet and treats underworld figures for money.

There are some terrific supporting actors, including a very young Charles Bronson and Timothy Carey (who was also in Kubrick’s The Killing) as two of the criminals.

It stars Sterling Hayden.

Although best known for his role as the mad US military commander, Brigadier General Jack Ripper in Kubrick’s Dr Stangelove, Hayden made a lot of films, including a lot of war movies and westerns I’ve never seen and a number of good noirs I have.

The latter include the granddaddy of heist films, John Huston’s 1950 classic, Asphalt Jungle, The Naked Alibi (1954), in which he played opposite Gloria Grahame, my favourite film noir bad girl, and with Kubrick again in the 1956 movie, The Killing.

Other films I’ve seen and liked him in include the first The Godfather film (1972), where he played the crooked Irish cop, McCluskey, and Johnny Guitar (1954), one of the strangest Westerns ever made, as Johnny ‘Logan’ Guitar.

Although Paramount Studio once billed him “the most beautiful man in movies”, I’ve never thought of him as especially attractive. He does, however, exude an intense, hard-nosed masculinity that perfectly fitted the noir sensibility of the late forties, early fifties. He was no pretty boy. He had a face that looked like it had seen things.

In Crime Wave, Hayden plays a tough cop, Detective Sims, who makes it his mission to take down the gang of ex-cons.

In Crime Wave, Hayden plays a tough cop, Detective Sims, who makes it his mission to take down the gang of ex-cons.

Hayden played a lot of cops, all of them cynical, world-weary men who don’t give a damn.

Why did he pull off these parts so well?

It wasn’t an act. Hayden actually didn’t give a goddamn about the movie business or the films he was in.

“Bastards, most of them,” as he once described his work, “conceived in contempt of life and spewn out onto screens across the world with noxious ballyhoo; saying nothing, contemptuous of the truth, sullen, lecherous.”

Hayden got his start in movies in 1941. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour he abandoned Hollywood, changed his name and enlisted in the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA. He ran German naval blockades to smuggle guns to Yugoslavian partisans and parachuted into Croatia for guerrilla activities.

The shit he must have seen and done.

After the war, he briefly joined the Communist Party and campaigned in support of the ‘Hollywood 19’ against the House of Un-American Activities Committee.

He only returned to film work only order to pay for his great passion, sailing boats. He even got jaded on politics, saying he regretted joining the Party and only did it so he could hang around drunk at parties and chase women.

The dismissive tone Hayden showed towards his own work aside, Crime Wave got me thinking I might have to stage a little festival in his honour. It’s been a while since I’ve seen The Godfather and Asphalt Jungle.

There are also a number of films of his I either haven’t seen or have and can’t remember, such the 1949 noir, Manhandled, Altman’s 1973 Marlowe spoof, The Long Goodbye (one of the few of his films Hayden thought worth a toss), and the 1969 movie Hard Contract. He also had a reasonably significant role in 1973 English sci-fi, The Final Programme, based on the novel by Michael Moorcock.

In Hard Contract, he was opposite Lee Remick and James Coburn who played a hit man who undertaking one last contract before he gets out of the game. I saw this one on TV ages and it’s currently unavailable on DVD. Anyone out there who knows where I might be able to get a copy, I’d appreciate it.

I dislike Altman’s self conscious take in The Long Goodbye. He has an interesting role to play on Bertolucci’s 1900…but among the noirs I’ve seen, The Killing is the most interesting as his role is so pivotal to the set up and the irony of the ending is something you relate to and that has a lot to do with his performance and presence.He is very much a narrative actor — a Brechtian would call him an epic performer — rather than one that works from an angsty inner core, so he never gets in the way of the plot unlike a lot of other acting from the same period. He was ‘outside’ his roles — like Mitcham and Robert Ryan — and when you look back he served Kubrick’s film work so well.

Interesting that Mitchum was also incredibly dismissive of his film career and detached from the pictures he made. Ryan less so, although he had a life and political interests outside of the films he played and often viewed those films as a vehicle to push the various causes he championed.

I am very interested in acting means and in the noirs the performance had to serve the storyline and the engineering of ‘the shot’. So as long as you were in frame and with the right shadow — then the rest was something else. So why spend all that energy researching your role and delving into its neurotic depths? Story, rather than character ego, ruled. A good example is the work of Marie Windsor — who I adore. But she only subtly varied her performances role to role –as did these guys you mention. The pitch was in the moment not some convoluted motivational history. (Windsor had another life as a sculptor).That gave them a sort of generic ‘Everyman’ character.

In the case of Hayden how much of what we appreciate about him is located in man-to-man tete a tetes? Dr Strangelove is a great example of that, isn’t it? “Bodily essences” has to be man talk, right? And in The Long Goodbye it is maybe over done. But that was his marker in the way that Mitchum had this ability to treat women as his equal and settle into the sort of an easy Jane Greer mode. It was a sort of default feminism — something that, I feel, rules the femme fatale persona (IE: let me out!I’m being drowned in this prison.). But of course there was this other motor — eg: Burt Lancaster’s noirs — which was passionate and angsty — very fire crackery .But there was all this Method School happening at the same time and I think noir films tended to dilute its impact and rule. You cannot imagine Dean or Brando in noir setup, right? They would demand too much screen focus — and besides, there were too many Communists and social realists in the noir business who wanted to talk about society rather than male angst a la Stanley Kowalski.

Take the gem, Murder By Contract…the guy, played by Vince Edwards, is sexless and without a profile. He is as much an enigma as Bogart is in High Sierra or Mitchum in Out of the Past.Obsession. Duty. Sure. But their deference is hard won and as far as we are concerned — as far as we know –they earned it.

I think Ryan did this better than the others. Stolid. Solid.And in a sense, there were these others that aspired to that state of grace– eg: Richard Widmark, esp in Night and the City (1950).

It was all about tragic figures on their way to the denouement and the question was how quietly they’d go into the night.

Dave, you are spot on.

The only real noir I could imagine Dean Martin playing would have been in real life. Late at night, sweating out the piss, thinking what the fuck am I doing and is Sinatra going to have me whacked because I stuck up for Sammy Davis Junior.

Pingback: Playing dirty: war as a criminal enterprise | Pulp Curry

Pingback: 50 Years of André de Toth's "Play Dirty" - CulturMag