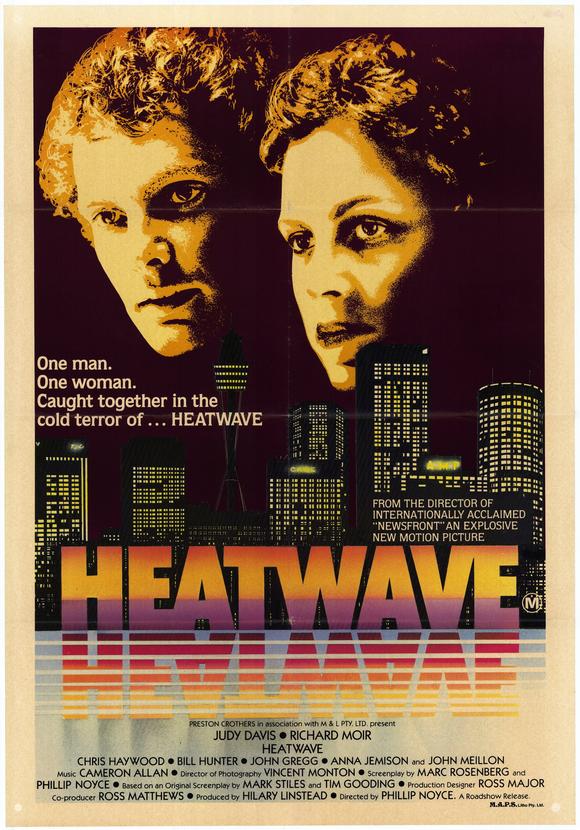

For years the 1982 movie Heatwave has languished in the shadow of director Phillip Noyce’s more recent and successful films.

It’s a great pity. Not only is Heatwave a dark, well-made thriller that can legitimately stake a place among the small group of Australian films with genuine noir sensibility, it is politically sharp-edged without coming across as either preachy or didactic.

Heatwave is one of two Australian films based loosely on the real life disappearance in 1975 of Juanita Nielson, a prominent local activist against mass development in the colourful vice quarter of inner Sydney known as Kings Cross. The other, Donald Crombie’s The Killing of Angel of Street, appeared the previous year. So close together were the two films that at one point they were reportedly both shooting at the different ends of the same inner Sydney street.

Heatwave takes place in the lead-up to Christmas and, as the title suggests, Sydney is sweltering after successive days of high temperatures. A group of Kings Cross residents are fighting attempts to demolish their houses to make way for a giant development named Eden, financed by businessman Peter Houseman (Chris Haywood).

For three years, young firebrand Kate Dean (Judy Davis) and Mary Ford, editor of the community newspaper, have led local opposition to Eden. In an effort to dramatically up the ante and bankrupt Houseman, the two women manage to secure the building union’s agreement to place construction bans on the proposed Eden site.

Although the protesters regard Eden as nothing more than a threat to their homes and community, others believe it represents a state of the art landmark in urban development. No one thinks this more than the brains behind the Eden’s design, architect Stephen West (Richard Moir).

With his million dollar Sydney harbour view and elegant European wife, West is far removed from the conflict being played out in the streets of Kings Cross. “The inner city is changing,” he tells the protestors. “Everyone wants to move closer to the centre and they’ll pay to do it. I’m sorry it’s just a natural process.”

However, through his contact with the residents, particularly Kate with whom he develops an unlikely relationship, this ironclad worldview gradually begins to shift. Houseman, meanwhile, is running out of money and patience. The head of the architectural firm West works for is also under pressure. The Eden project now comprises 90 per cent of his business. If it goes under, so will he.

In an effort to placate the union, Houseman offers to modify Eden’s design to incorporate the contested dwellings. “What your talking about is like cutting off a foot.” West implores to him. “It will destroy the balance and grace of the whole building.”

Then Dean’s co-conspirator, Mary Ford, disappears. The police are dismissive, telling Dean that her friend has probably just gone on holidays. Despite official disinterest, Dean investigates further, at which point someone sets fire to the last of the remaining houses due for demolition, killing a long-time resident. Police raid Dean’s house, finding a detonator and a stick of dynamite.

West believes the destruction of the homes offers a chance to revert back to the original design, only to be told by Houseman’s sleazy lawyer, Lawson, that the financial situation has changed. Peter realises that Houseman never intended to build Eden, that all the architect’s work was just a cover for the kind of mass concrete development he loathes.

From here on the plot lines multiply. Lawson is brutally murdered and Houseman flees the country after his company is taken over by a shadowy interest called Selco Nominees linked to a malevolent Kings Cross strip club owner. The movie reaches its conclusion on New Years Eve as the heatwave breaks and rain engulfs the city.

Coming off the huge success of his first feature film, Newsfront, in 1978, Heatwave confirmed Noyce’s reputation as a director to watch. The film works well on many levels, particularly the push-pull attraction between the characters played by Davis and Moir.

Coming off the huge success of his first feature film, Newsfront, in 1978, Heatwave confirmed Noyce’s reputation as a director to watch. The film works well on many levels, particularly the push-pull attraction between the characters played by Davis and Moir.

Davis, in only her third role, excels as Dean, the radical with a patrician background. With her short spiky hair and t-shirts emblazoned with radical slogans she’s every bit a “mouthy sheiler”, as she’s called at one point. It’s easy to see from this film how she went on to bigger and better things.

Heatwave was unfortunately the peak of Moir’s career. A talented actor, Moir manages to portray West as a man who is cool, almost cold blooded, at the same time as being obsessive about his architectural vision.

They are supported by a great selection of Australian acting talent, including John Meillon, Bill Hunter, Dennis Miller, and Chris Hayward who is especially good as Houseman, a self-made millionaire who has lost none of his used car salesman attitude. Haywood plays the character for all it’s worth, without resorted to clichés.

Noyce has commented in subsequent interviews on how Heatwave belongs to a different era of Australian cinema, when directors were prepared to take more risks, and that if he’d made it now it would be a very different film.

Heatwave is indeed unusual in that so many sub-plots and characters swirl about; yet, it works, the dense, complex story mirroring the murky, unresolved feel of the events that inspired it.

Juanita Nielson had disappeared only seven years earlier and the events surrounding the crime were still fresh in the public imagination. Nielson had been the target of threats against her life for some time over her role as one of the leaders of Kings Cross residents opposed to the redevelopment of their suburb.

She was reportedly lured to the nightclub of a prominent vice identity with the promise of advertising for the small community newspaper she edited. Her handbag and other personal effects were later found near a freeway but she was never seen again. That the crime was never solved surprised few given the corrupt state of the New South Wales police at the time. Indeed, one of the culprits in her disappearance was rumoured to be a senior cop.

The very last scene in Heatwave, of a female body (obviously the missing anti-development campaigner Ford) bobbing to the surface of an overflowing storm water drain on the Eden building site are a variant of the widely held view that Nielson was murdered and her body hidden in the concrete foundations of the building she opposed.

Not only did Noyce take risks with the plot. The tone of the film, dominated by the contrast between shadowy dark nights and glaringly sunny days, was unusual for Australian cinema at the time.

Additional layers of texture are added by the oppressive heat and the ever-present background hum of noise, the radio news, police sirens in the distance, the shouts of protesters and partying crowds. The cumulative impact of all this is constant feeling of nagging anxiety. Events, either peripheral or central to the story are always happening somewhere else, just out of sight of the viewer.

The greatest strength of Heatwave is the way it refuses to answer every question and neatly wrap up every plot line. In the film, as in the events it was based on, we never get the full story.

A version of this article original appeared as one of Back Alley Noir’s Film Noir of the Week.

Photograph: Australian National Film and Sound Archive.

I remember seeing heat wave. The story line is of a suburban war. The tension and underlying uneasiness and anxiety I felt at the time is still with me. It really is a foreboding of the future destruction of our lovely old houses/cottages etc which as we see has come to pass. Developers design how we live and bring up our children (inside) and the dwellings are made ready to become tomorrow’s slums which keep the developers in business. This is a very atmospheric and as it turns out a nihilistic film. So energetic and raw and savage in the conflicts . Very edgy. I still bring this film up when discussing the ugliness of our environment with these shitty housing projects.

It unfortunately seems too late to stop the corruption and bad taste of those with money.