There’s a lot of justified hype about the period of Australian film from the mid-seventies to the mid-eighties known as “Ozploitation”, when the creation of film funding bodies and the introduction of government tax breaks to encourage investment in the industry saw an explosion of local production.

There’s a lot of justified hype about the period of Australian film from the mid-seventies to the mid-eighties known as “Ozploitation”, when the creation of film funding bodies and the introduction of government tax breaks to encourage investment in the industry saw an explosion of local production.

But there was one genre of movie the Ozploitation period did not do well or often – crime.

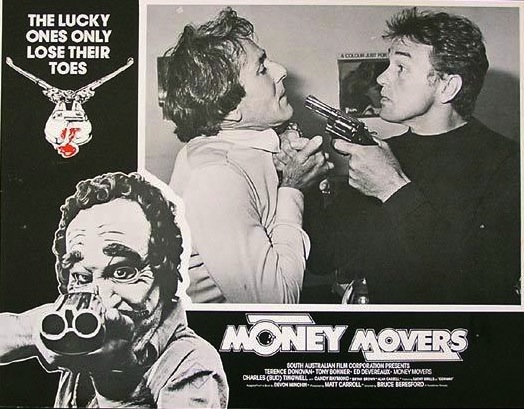

One of the few exceptions is Bruce Beresford’s heist movie, Money Movers. Adapted from the novel of the same name by an ex-security officer, like a lot of films from the Ozploitation period, Money Movers completely flopped when it was released in 1979.

Unlike like a lot of the Ozploitation movies that have since gone on to enjoy critical and cult acclaim, Money Movers remains little known or appreciated, despite a dvd version being released in 2004. This is a pity because Money Movers is proof Australia could knock out a noir as gritty and multi-layered as the best of them.

Its hardboiled feel is established in the opening scenes, muster time in the counting house of Darcy’s Security Services. The armoured car drivers exchange jokes and take a last drag on their cigarettes before going on the weekly bank run. Two of them, Brian Jackson (iconic Australian actor Bryan Brown) and his brother, Eric (Terence Donovan), head of security at Darcy’s, pause to observe money being unloaded from a truck with particular interest.

This is juxtaposed with shots of management, or the “armchair drivers” as those on the shop floor derisively refer to them, and images of the (then) modern paraphernalia of security in operation: mesh grills being electronically lowered, lights flashing, doors being buzzed open.

On the road, one of the trucks parks for the drivers to a take a lunch break. On their return, they are jumped by men wearing clown masks and brandishing sawn off shotguns. The only man to resist is Dick Martin (Ed Devereaux). He gives a good account of himself before being clubbed. His resistance marks him out someone who won’t be intimidated even when he’s dealing with a bandit who has just gunned down an innocent bystander in broad daylight.

The robbers are next seen pulling into an old garage. No sooner have they cracked open their first celebratory beers than they are finished off by a henchman working for the mastermind behind the operation, Henderson (another veteran Australian actor, Charles ‘Bud’ Tingwell), who has no intention of sharing the take.

Meanwhile across town, a secretary hands the CEO of Darcy’s a note (made up of cut and pasted newspaper letters, no less), informing them the counting house will soon be robbed. The note forces management to fast track new security measures – if they can get them past the opposition of the local trade union.

They are not the only ones worried. The Jackson brothers along with the emphysemic head of the local union are planning to rob the counting house and are not happy with the prospect of competition.

Eric Jackson has been working on the job for five years, taking his time, making sure everything is right, much to the chagrin of his hot-headed brother. “By the time you’re ready, well be rushing into the counting house in wheel chairs,” Brian tells his cautious older brother. Now their hand has been forced and they have to move quickly.

As they talk, the three men leaf through the personnel files of new recruits to the company for some clue about who might be trying to muscle in on their job. Their main suspect is Leo Bassett (Tony Bonnor), a young urbane man patently out of place patrolling industrial back lots in the middle of the night.

To bank roll their plan, Eric Jackson knocks over a cosmetics factory patrolled by Darcy’s, in the process killing one of his own security guards. Next he prowls Bassett’s pad for evidence linking him to the note, unaware it is also under surveillance by Henderson’s goons. They capture Jackson, find the replica of the Darcys’ armoured car he and his brother are working on, and realise what they are up to.

With the help of some bolt cutters, Henderson persuades the Jackson brothers to cut him in as a partner. Henderson’s terms are simple: he seconds some of his men to help out with the job and takes 60 per cent of anything stolen in exchange for helping get the brothers out of the country when it is over. It’s not a great deal, especially given that we’ve already seen how Henderson deals with partners.

Using a union meeting as cover, the brothers attempt the robbery. It almost comes off until Dick Martin fresh from the beating he endured during his earlier attempt to protect the company’s money, notices something amiss. Needless to say, like most heist films it all ends very badly.

The feel of the Money Movers is straight down the line noir. The city of Sydney is anonymous as a location. The story takes place in truck lots, factory floors, container yards and neon lit streets, there’s not an opera house or expanse of blue water in sight. On the few occasions the movie takes us into larger, more brightly lit locations, the characters seem tense and uneasy.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of Money Movers is the way Beresford executes the classic noir theme of the paper-thin line between good and bad. Corruption is so pervasive, so matter a fact, it’s hardly commented on. Management complain about the girls in the counting room slipping notes into their underwear. Before he’ll lift a finger, Ross the policeman investigating the note threatening to rob the counting house casually shakes down Darcy’s human relations manager for a bribe. “Might be a bit costly”, Ross says about chasing down leads. “Not real orthodox stuff.” Even Dick Martin is tainted, framed by his former colleagues and pushed out of the police force after 24 years because he wouldn’t take bigger bribes.

The blurring of morality extends to modern business methods. Darcy’s management are more worried about the impact of the latest armoured car robbery on their insurance premiums than the safety of their employees. The CEO ponders aloud whether they should try and get some younger guards, “ex-Vietnam boys”, only to be informed they’re considered too trigger happy. Besides getting a better class of guard would break unofficial company policy only to employ applicants who fail the test: they are the only ones who won’t get bored with the job.

Flush with money made from selling drugs, liquor and sex to visiting American GIs during the Vietnam War, the seventies were a time of massive corruption across much of the eastern seaboard of Australia. The nexus between criminals, commerce, sections of the labour movement and police was tight. Illegal businesses flourished often under the direct patronage of corrupt police.

Against these forces, amateurs like Eric and Brian Jackson don’t stand a chance, no matter how quick on their feet or good with their fists they are. Beresford doesn’t waste much time explaining why these men want to rob their employer. For the older brother, an ex-racing car driver now trapped in an unhappy marriage, it’s about recapturing some sense of being on the edge. His younger brother just wants the good life. All we know about the aging union hack is an old black and white photograph of an Asian woman and his promise to come back to her.

The film combines classic elements of noir with some uniquely Australian characteristics. The class divide is starkly drawn, reinforced through out the film by images of wealth and money. The Australian economy was on the verge of recession in the late seventies, unions represented over half the working population (now it is about 20 per cent), and the view that management and workers were not on the same side wasn’t as anachronistic as it sounds now. The desire of the Jackson brothers to rip management off, to get what they have, is just a given. Even the crime boss Henderson is a victim of the economic times, masterminding armed robberies for funds to refurbish his textile factory that went belly up when government lifted import restrictions.

Given the milieu it depicts, the Money Movers has a male feel and aggression and violence are always close to the surface. The men are in charge, the women relegated to harassed secretaries, angry wives, and bits on the side. Leo Bassett, the man the Jackson brothers suspect of being behind the note, is not only an outsider, he’s branded a ‘poofter’ by Brian Jackson because it states in his personnel file that he likes music and poetry – the kiss of death in seventies Australian working class male culture.

Those who do try to do their job and refuse to compromise, like ex-cop Dick Martin, get little in return. At the film’s end, as Martin is being wheeled out of the counting house on an ambulance gurney after nearly being killed foiling the Jackson brother’s robbery, the corrupt cop Ross tells him: “Get over this and they’ll stick a medal on you and put you back on award wages”.

A little piece of metal and a minimum wage job – the best deal a hero is likely to get in Money Movers.

This piece originally appeared in Back Alley Noir’s Film Noir of the Week in June 2010.

I shall definitely be tracking this one down Andrew – so good to know I am not only Bryan Brown tragic around

Bernadette, no you most definitely are not. Do watch this one. Not only is it a great period piece but pound for pound it’s one of the best heist movies I have ever seen.

Pingback: Wish You Were Here: middle class people behaving badly | Pulp Curry

i just saw this today for free on Tubi. First rate little flick, film noir legend Charles McGraw would approve.

Kind of jarring for anyone growing up with Skippy to see Ed Devereaux shot.

Skippy co-star Tony Bonner also is in this flick, and knowing his resume I didn’t buy his cover as just another guard whose fellow workers intimated was a wimp, so the plot twist concerning him wasn’t a shock. Another Skippy veteran appearing is Jeanie Drynan. By the way, “They’re a Weird Mob” boasts the entire Skippy cast except for Gary Pankhurst, and this was before the series was even made.

The impact of the very last scene in “Money Movers” is lessened by anyone who has seen the “Underbelly” series or read the books. It might have been a shock in 1978 but not now.

Pingback: Dishing up Pulp Curry in a new way | Pulp Curry

Pingback: Dishing up Pulp Curry in a new way: why I am starting a Substack newsletter | Pulp Curry